Paper Review: Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data

Introduction

In this post, I will review the paper Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data1, by Brendan McMahan and others, published in 2016. This paper coined the term Federated Learning, and set the basis for the field. This paper represents one of the many contributions of Google to the field of Machine Learning… Let’s get started!

Motivation

The main motivation for this paper is the following:

- We have a lot of data, but it is distributed across many devices.

- We want to train a model on this data, but we cannot centralise it. This can be due to privacy concerns, because the data comes, for example, from users’ devices, or because it is too expensive to centralise it.

The solution proposed by the authors is to train the model in a decentralised way, without centralising the data. This is the main idea behind Federated Learning.

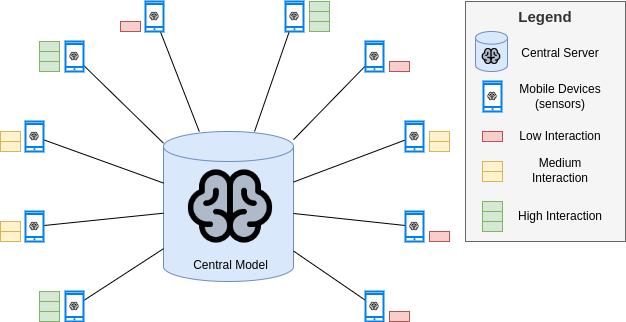

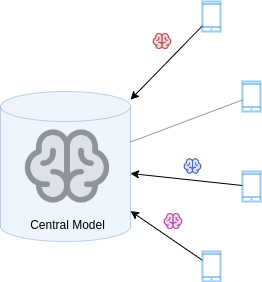

In the following image, we can observe the setup of the problem:

We observe that there are several devices with a local copy of the central model. Each device captures data from its environment, and uses the local model to make predictions.

Now, due to the distributed nature of this setup, and considering that each device has a different environment (for instance, the users producing the data are different), the data presents the following properties:

- Non-IID: the data is not identically distributed across the devices. That is, each user can have a different behavior, and therefore, the distribution of data can vary across devices.

- Unbalanced: the data is not balanced across the devices. That is, each device can have a different amount of data, depending on user’s usage. This is depicted in the previous image.

Moreover, the Google team also considered the setup to be:

- Massively distributed, with a large number of devices. They expected to have more devices than data points per device.

In addition, their setup was conceived for mobile devices, which have:

- Limited communication, since they are usually offline or in a limited (or expensive) network.

Formalisation of the problem

The authors formalised the problem as follows:

- There is a synchronous update scheme, that goes in rounds of communication between the devices and the server.

- We have a set of \(K\) devices, each with a local dataset \(D_k\).

- At each round, a random fraction of devices, \(C\), is selected to participate in the training. The server sends the current model to the selected devices.

- Each device trains the model on its local data, and sends the updated model to the server.

- The server aggregates the models, and sends the updated model to the devices.

Their approach works with any objective function of the form: \[ \min_{w \in \mathbb{R}^d} f(w), \] where \(f\) is a finite-sum function of the form: \[ f(w) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f_i(w), \] where \(f_i\) is the loss function of the \(i\)-th data point.

The authors proposed the following objective function: \[ f(w) = \sum_{k=1}^K \frac{n_k}{n} F_k(w), \] where \(n_k\) is the number of data points in device \(k\), and \(F_k\) is the loss function of device \(k\).

Related work

This paper is the first one to propose the idea of Federated Learning, with the aforementioned setup. However, there are several related works that are worth mentioning, which studied the idea of distributed learning in more controlled settings:

-

McDonald et al.2 showed that it was possible to train a central perceptron by averaging the weights of several local perceptrons, each trained on a different subset of the data. Povey et al.3 applied this technique for NLP tasks. Zhang et al.4 proposed a similar approach for training deep neural networks, using ‘soft’ averaging of the weights. These approaches and other similar ones only consider a cluster of machines, with balanced and IID data.

-

Neverova et al.5 discussed the advantages of keeping user data inside their devices.

-

Some previous work focused on how to efficiently perform distributed training under the assumption of convexity, a small number of clients and IID data. For example, the work of Balcan et al.6 and Zhang et al.7.

-

Dean et al.8 had proposed a way to perform asynchronous and distributed SGD, but it was too computationally expensive for the setup of this paper.

The algorithm: Federated Averaging

The authors defined the algorithm called Federated Averaging, which depends on the following hyperparameters:

- \(C\): the fraction of devices that participate in each round.

- \(E\): the number of local epochs that each device performs.

- \(B\): the minibatch size used by each device. \(B=\infty\) means that the device uses the whole local dataset as a minibatch.

Note that for a client \(k\), the number of SGD steps is \(E \cdot \frac{n_k}{B}\).

The algorithm is the following:

Initialize \(w_0\)

for each round \(t = 1, 2, ...\) do

\(m \leftarrow \max(C\cdot K, 1)\)

\(S_t \leftarrow\) (random set of \(m\) clients)

for each client \(k \in S_t\) do in parallel

\(w_{t+1}^k \leftarrow\) ClientUpdate(\(k, w_t\))

\(m_t \leftarrow \sum_{k\in S_t} n_k\)

\(w_{t+1} \leftarrow \sum_{k\in S_t} \frac{n_k}{m_t} w_{t+1}^k\)

ClientUpdate(\(k, w\)): // Run on client \(k\)

\(\mathcal{B} \leftarrow\) (split \(D_k\) into batches of size \(B\))

for \(i = 1, 2, ..., E\) do

for batch \(b \in \mathcal{B}\) do

\(w \leftarrow w - \eta \nabla f_k(w; b)\)

return \(w\) to server

The authors also proposed a variant of the algorithm, called Federated SGD, which is the same algorithm, but with \(C=1\), \(E=1\) and \(B=\infty\). That is, each round, all devices perform a full SGD step on their local data, and then the server averages the models.

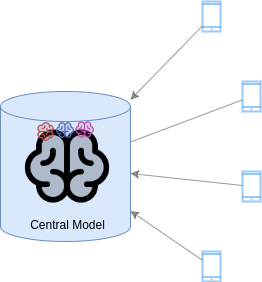

The algorithm is illustrated in the following images:

-

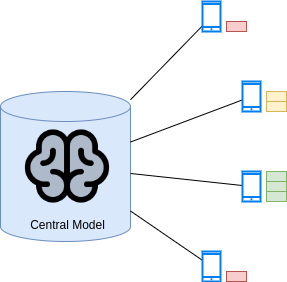

The intial setup is the following:

-

The server sends the current model to the selected devices. Here, \(C=0.75\), so \(m=3\).

-

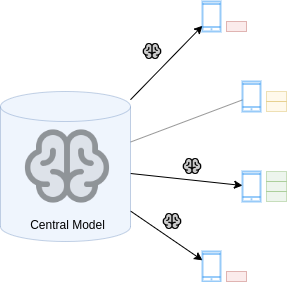

Each device trains the model on its local data, for \(E\) epochs, with a minibatch size of \(B\).

-

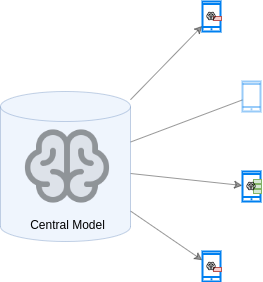

The devices send the updated models to the server.

-

The server aggregates the models.

-

The process is repeated until the number of rounds is reached.

Experiments and results

Datasets

The authors performed experiments on two datasets:

- MNIST: a dataset of handwritten digits, with 60,000 training images and 10,000 test images. Partitioned in two different ways:

- IID: the data is shuffled and partitioned evenly across 100 clients, with 600 images per client.

- Non-IID: the data is sorted by label, divided into 200 shards of 300 images each, and then assigned to 100 clients, with two shards per client. Notice how most clients will only have images of two digits, and some clients may even only have images of one digit. Note, however, that the data is still balanced across clients, since each client has the same number of images.

-

Shakespeare: a dataset of Shakespeare’s writings, where each client is a character in a play, producing a dataset with 1146 clients. The data is non-IID, since each client represents a different character, and unbalanced, since each character has a different number of lines. For each client, the first 80% of the lines are used for training, and the last 20% for testing, accounting for 3,564,579 characters in the training set and 870,014 characters in the test set.

They also considered a variant of the dataset, where the data is IID, by shuffling the lines and partitioning them evenly across clients, also with 1146 clients.

Models

The authors used three models:

- MLP with two hidden layers of 200 units each, with ReLU activations. Applied to the MNIST dataset. (MNIST-2NN)

- CNN with two 5x5 convolutional layers of 32 and 64 filters, respectively, with ReLU activations, followed by max-pooling, and a fully connected layer of 512 units, with ReLU activation. Applied to the MNIST dataset. (MNIST-CNN)

- LSTM with two layers of 128 units each, with ReLU activations. Applied to the Shakespeare dataset and trained to predict the enxt character with an unrolled sequence length of 80. (Shakespeare-LSTM)

Experiments

The authors performed several experiments, which I will summarise here:

- Increasing parallelism: they varied the parameter \(C\), in different setups, and measured the number of communication rounds needed to reach a certain accuracy.

Observe the results in the following tables:

2NN IID Non-IID C B = \(\infty\) B = 10 B = \(\infty\) B = 10 0.0 1455 316 4278 3275 0.1 1474 (1.0x) 87 (3.6x) 1796 (2.4x) 664 (4.9x) 0.2 1658 (0.9x) 77 (4.1x) 1528 (2.8x) 619 (5.3x) 0.5 --- 75 (4.2x) --- 443 (7.4x) 1.0 --- 70 (4.5x) --- 380 (8.6x) CNN, E = 5 IID Non-IID C B = \(\infty\) B = 10 B = ∞ B = 10 0.0 387 50 1181 956 0.1 339 (1.1x) 18 (2.8x) 1100 (1.1x) 206 (4.6x) 0.2 337 (1.1x) 18 (2.8x) 978 (1.2x) 200 (4.8x) 0.5 164 (2.4x) 18 (3.1x) 1067 (1.1x) 261 (3.7x) 1.0 246 (1.6x) 16 (3.1x) --- 97 (9.9x) We can conclude that:

- Increasing parallelism generally leads to faster convergence.

- The effect of increasing parallelism is more pronounced in the non-IID case.

- Increasing computation per client: they fix \(C=0.1\), and added more computation per client, by decreasing \(B\) and increasing \(E\), and measured the number of communication rounds needed to reach a certain accuracy.

The results are shown in the following table:

MNIST CNN, 99% ACCURACY E B IID Non-IID 1 \(\infty\) 626 483 5 \(\infty\) 179 (3.5x) 1000 (0.5x) 1 50 65 (9.6x) 600 (0.8x) 20 \(\infty\) 234 (2.7x) 672 (0.7x) 1 10 34 (18.4x) 350 (1.4x) 5 50 29 (21.6x) 334 (1.4x) 20 50 32 (19.6x) 426 (1.1x) 5 10 20 (31.3x) 229 (2.1x) 20 10 18 (34.8x) 173 (2.8x) SHAKESPEARE LSTM, 54% ACCURACY E B IID Non-IID 1 \(\infty\) 2488 3906 1 50 1635 (1.5x) 549 (7.1x) 5 \(\infty\) 613 (4.1x) 597 (6.5x) 1 10 460 (5.4x) 164 (23.8x) 5 50 401 (6.2x) 152 (25.7x) 5 10 192 (13.0x) 41 (95.3x) We can conclude that:

- Increasing computation per client generally leads to faster convergence.

- The effect of increasing computation per client is more pronounced in the IID case when the data is balanced, but in the non-IID case, the effect is more pronounced when the data is unbalanced, which is the case of the Shakespeare dataset and the case the authors expected to find in real-world scenarios.

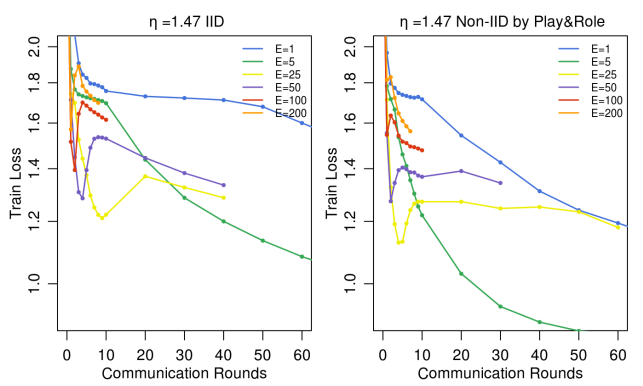

-

Can we overoptimize on the client datasets?: they fixed \(C=0.1\) and \(B=10\), and varied \(E\), measuring the overall accuracy of the model. The results are the following:

Results of the experiment1. We can conclude that:

- Increasing \(E\) leads to better performance, but only up to a certain point.

- After that point, the performance can get stuck or even decrease.

Conclusion

In this paper, the authors proposed the idea of Federated Learning, and showed that it was possible to train a model in a decentralised way, without centralising the data, even when the data was non-IID and unbalanced across devices. They showed that this can be done using relatively few communication rounds.

They set the basis for the field of Federated Learning, enabling for enhanced privacy and reduced communication costs, and opened the door to many other works.

The state of Federated Learning today

Since this paper was published, many other works have been published, improving the algorithm, and proposing new applications. For instance:

- Adaptive Federated Learning9 enhances the algorithm by designing adaptive optimization methods in a federated setting, like Adam, Adagrad, etc.

- Federated Learning with Differential Privacy10 enhances the security of the algorithm by adding differential privacy to the training process, to protect the privacy of the users. The authors showed that there exists a trade-off between privacy and accuracy, and proposed a method to find the optimal point in this trade-off, given a privacy budget.

- Sparse Ternary Compression11 enhances the algorithm by compressing the model, to reduce the communication costs.

- FL, in general, shows very promising results in the field of IoT and Edge Computing, where the devices are usually resource-constrained, and therefore, the communication costs are very important and the computing power is limited in a single device, but the great amount of devices collecting and processing data can be used to train a model12.

References

-

Brendan McMahan, Eider Moore, Daniel Ramage, Seth Hampson, and Blaise Aguera y Arcas. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, PMLR: 1273-1282, 2017. ↩ ↩2

-

Ryan McDonald, Keith Hall, and Gideon Mann. Distributed training strategies for the structured perceptron. In NAACL HLT, 2010. ↩

-

Daniel Povey, Xiaohui Zhang, and Sanjeev Khudanpur. Parallel training of deep neural networks with natural gradient and parameter averaging. In ICLR Workshop Track, 2015. ↩

-

Sixin Zhang, Anna E Choromanska, and Yann LeCun. Deep learning with elastic averaging sgd. In NIPS. 2015. ↩

-

Natalia Neverova, Christian Wolf, Griffin Lacey, Lex Fridman, Deepak Chandra, Brandon Barbello, and Graham W. Taylor. Learning human identity from motion patterns. IEEE Access, 4:1810–1820, 2016. ↩

-

Maria-Florina Balcan, Avrim Blum, Shai Fine, and Yishay Mansour. Distributed learning, communication complexity and privacy. arXiv preprint arXiv:1204.3514, 2012. ↩

-

Yuchen Zhang, John Duchi, Michael I Jordan, and Martin J Wainwright. Information-theoretic lower bounds for distributed statistical estimation with communication constraints. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2013. ↩

-

Jeffrey Dean, Greg S. Corrado, Rajat Monga, Kai Chen, Matthieu Devin, Quoc V. Le, Mark Z. Mao, Marc’Aurelio Ranzato, Andrew Senior, Paul Tucker, Ke Yang, and Andrew Y. Ng. Large scale distributed deep networks. In NIPS, 2012. ↩

-

Sashank Reddi, Zachary Charles, Manzil Zaheer, Zachary Garrett, Keith Rush, Jakub Konečný, Sanjiv Kumar, H. Brendan McMahan. Adaptive Federated Optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.00295, 2020. ↩

-

Kang Wei, Jun Li, Ming Ding, Chuan Ma, Howard H. Yang, Farhad Farokhi, Shi Jin, Toni Q. S. Quek, H. Vincent Poor. Federated Learning With Differential Privacy: Algorithms and Performance Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 15:3454-3469, 2020. ↩

-

Felix Sattler, Simon Wiedemann, Klaus-Robert Müller, Wojciech Samek. Robust and Communication-Efficient Federated Learning From Non-i.i.d. Data. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 31:3400-3413, 2020. ↩

-

Shiqiang Wang, Tiffany Tuor, Theodoros Salonidis, Kin K. Leung, Christian Makaya, Ting He, Kevin Chan. Adaptive Federated Learning in Resource Constrained Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, 37:1205-1221. 2019. ↩